Date Finished: September 26th 2021

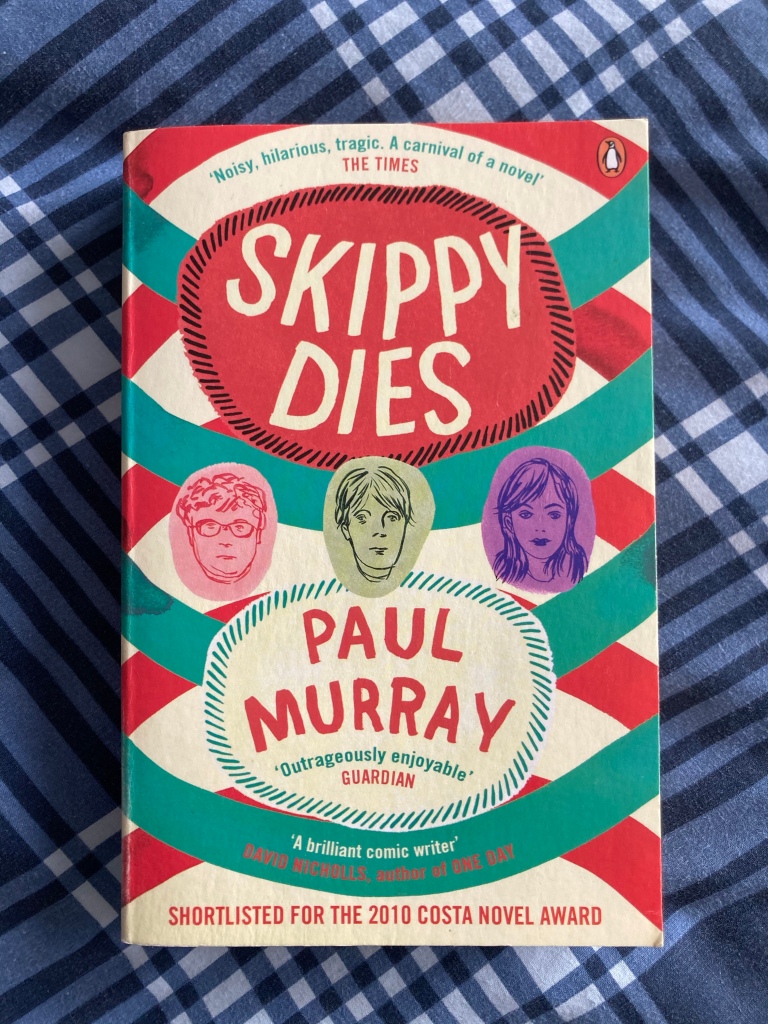

Serendipity, eh? You never know when it’s gonna strike. I spotted Skippy Dies in a second hand book shop, it’s exuberant cover caught my eye. I think I’ve heard its author, Paul Murray’s name before, but I was, for all intents and purposes, totally unfamiliar with both author and book. I read over the blurb and a bit of the opening and something about it felt right, like maybe this was the book I’d been looking for. I’d been in (yet another) reading slump, and a near-700 page novel might not have been the best thing to drag me out of that, but I decided to take a chance on it.

“Gradually the awful truth dawns on you: that Santa Claus was just the tip of the iceberg – that your future will not be the rollercoaster ride you’d imagined, that the world occupied by your parents, the world of washing the dishes, going to the dentist, weekend trips to the DIY superstore to buy floor tiles, is actually largely what people mean when they speak of ‘life’.”

On the first page of Skippy Dies, Skippy dies. He chokes to death mysteriously in Ed’s doughnut shop. He’s a student at prestigious public school Seabrook College in Dublin; is friend to his genius roommate Ruprecht; is bullied by Carl, the school psychopath; is in love with Lori, the frisbee-throwing beauty from the adjacent St Brigid’s; is student of history teacher Howard, who has his own love and life crises to deal with; and is diligent member of the swim team headed by the crippled coach Tom Roche. The events leading up to and falling out from Skippy’s untimely passing are recounted to solve the mystery of his tragic death.

Skippy Dies rollicks along at pace. Whilst the eponymous Skippy is our main concern, Murray also interweaves the story with the lives of others, telling the story from two other main perspectives: Ruprecht, who’s determinedly attempting to solve string theory with an Optimus Prime toy and a lot of tinfoil; Howard, whose life, relationship and career have lost all meaning until the beautiful Miss McIntyre takes over geography classes. But we also take frequent jaunts into the troubled mind of Carl, who’s dealing drugs with Barry; the guilt of the elderly tyrannical Father Green, and the teenage confusion of Lori. There’s a vast ensemble cast of characters rounding the novel out, many of whom are fun caricatures, the kind we often encounter in life, acting as a counterpoint to the psychological turmoil of our leads.

‘I mean, we go to a film, we eat dinner, we fight, we joke, we go out with friends – sometimes it seems like none of it really adds up to anything. It’s just one thing after another. And twenty-four hours later I’ve forgotten it all…. I’m not saying it’s bad. It’s just now how I expected my life would be.’

‘What did you expect?’

… ‘I suppose – this sounds stupid, but I suppose I thought there’d be more of a narrative arc…. A direction. A point. A sense that it’s not just a bunch of days piling up on top of each other.’

Murray’s writing is inhabitable; the characters are written with an emotional acuity and authenticity that makes them a joy to read, their neuroses and desires and regrets permeating the text at all times. His style reminds me of Zadie Smith, particularly White Teeth, and I suppose Murray belongs to that same school of hysterical realism. It is “generous, heartfelt, funny and sad” as the Irish Times boasts, and I never trust the pull quotes, especially when they try to sell a book as funny, but Skippy Dies is all those things at once. The way it can turn on a dime from hilarious to affectingly emotional is something to behold. There really are some quite profound and lovely meditations in the novel, and his pet themes of love and meaning are ones that I always find resonant.

“He is thinking about asymmetry. This is a world, he is thinking, where you can lie in bed, listening to a song as you dream about someone you love, and your feelings and the music will resonate so powerfully and completely that it seems impossible that the beloved, whoever and wherever he or she might be, should not know, should not pick up this signal as it pulsates from your heart, as if you and the music and the love and the whole universe have merged into one force that can be channelled out into the darkness to bring them this message. But in actuality, not only will he or she not know, there is nothing to stop that other person from lying on his or her bed at the exact same moment listening to the exact same song and thinking about someone else entirely – from aiming those identical feelings in some completely opposite direction, at some totally other person, who may in turn be lying in the dark thinking of another person still, a fourth, who is thinking of a fifth, and so on; so that rather than a universe of neatly reciprocating pairs, love and love-returned fluttering through space nicely and symmetrically like so many pairs of butterfly wings, instead we get chains of yearning, which sprawl and meander and culminate in an infinite number of dead ends.”

The novel is bifurcated by Skippy’s demise. The run-up to the titular act is an absurd romp through the main players at the school, fizzing with irreverence and potentiality; even when doors close, when pathos breaks through the giddy facade, it does so with an undercurrent of whimsy. After Skippy’s death, however, the novel becomes discombobulated, somewhat like the latter half of Catch-22, when the true horror begin to take its toll on Yossarrian, and the grim humour that has predominated leans further on the grim (though it’s still very funny). These are the wrecks left behind, this is what death does to people; to friends, to teachers, to enemies, to lovers, to the people who never knew who they were part of that story, to the community that never knew the deceased but acutely feels the loss. I was reminded, too, of the characterisation of Pynchon’s novels being marked by “decoherence events”, wherein a certain moment causes everything to fall apart, causes the irreverent absurdity to take on a much darker, more impactful stance. That’s what Murray is working with here and he pulls off the trick with aplomb.

“Why can’t we fall in love with a theory? Is it a person we fall in love with, or the idea of a person? So yes, Ruprecht has fallen in love. I was love at first sight, occurring the moment he saw Professor Tamashi present that initial diagram, and it has unfolded exponentially ever since. The question of reason, then, the question of evidence, these are wasted on him. Since when has love ever looked for reasons, or evidence? Why would love bow to the reality of things, when it creates a reality of its own, so much more vivid, wherein everything resonates to the key of the heart?”

Murray captures the angst of adolescent well, Skippy’s simultaneous profound connections and growing isolation feel familiar, and he understands the naivety and stupidity of teenagers, perhaps best displayed by, of all people, Ruprecht. Grief is also here in spades, but few people actually sit down and mourn Skippy; rather the tragedy of his death hits in a variety of ways; where Ruprecht eats, Lori starves; where Howard seeks justice, the school wants to memorialise. The feeling that there is no meaning in so many people’s lives is punctured by the enormity of Skippy’s passing, and yet finding meaning here, making sense of it, is so difficult. Even when something clearly meaningful comes along, doing something meaningful with it is difficult. Howard turns to history, that sense of shared connection, with mixed results; Ruprecht turns to an increasingly outdated and spiritual form of science. Murray explores much more, too: the sins of the Church versus the emergent sins of the business class; quarter and mid-life crises; and, perhaps above all, connection, feeling any sort of connection to the people around us, whether we’re truly physically alone, or merely afloat emotionally. Murray crams so much of life into a story about death, and I can’t help but admire it hugely.

“He realizes he’s imagined her suspended in some atemporal state; only now does it hit him that in the moment before his call, and all the moments before that for the last weeks, she’s been doing other things, living through days that he knows nothing about, just as before he met her there were thousands more days as real to her as the hand before her face that he will never have an inkling of, in which he never figured as an idea.”

I tend to be overly cautious in giving 5 stars (or a 9 or 10/10) to books these days, particularly fiction. Part of that is to do with staying power. White Teeth I revised up to an all-time favourite when I realised how it had lingered with me. Time will tell if Skippy Dies will do the same; it’s undoubtedly a frenetic work of postmodern mania, deconstructing the sins of the church and the inadequacy of science to expose the gulf between the two. A compromise between science and spirituality has often been touted as the best route for understanding the world, but it seems to miss the point that if science can’t totally explain everything and spirituality can’t offer total solace, then perhaps there’s simply something missing. Perhaps we’ll never find what that is. It might be love, Murray certainly gives credence to that notion, but that still might not be enough. You can’t explain the world with love. The world moves on from love. But maybe the strings that hold this world together hold something more; those invisible connections endure. That’s Murray’s theory. I hope he’s right.

“To hear people talk, you would think no one ever did anything but love each other. But when you look for it, when you search out this love everyone is always talking about, it is nowhere to be found; and when someone looks for love from you, you find you are not able to give it, you are not able to hold the trust and dreams they want you to hold, any more than you could cradle water in your arms. Proposition: love, if it exists at all, does so primarily as an organizing myth, of a similar nature to God. Or: love is analogous to gravity, as postulated in recent theories, that is to say, what we experience faintly, sporadically, as love is in actuality the distant emanation of another world, the faraway glow of a love-universe that by the time it gets to us has almost no warmth left.”

Skippy Dies is, quite simply, a joy. I was gripped through 660 pages of nonsense science, eccentric characters, tragicomic grief, profound meditations, and zany happenings. It’s a novel that stands shoulder-to-shoulder with some of the best modern comic fiction, that of Zadie Smith and Jonathan Coe. It brims with the disorder and irrationality of everyday life and attempts to reconcile that structurelessness with the narratives we tell ourselves. It’s a bold, brash, infinitely funny feat; the right novel at the right time, and possibly my favourite novel I’ve read this year. Serendipity, eh?

8.5/10